The coronavirus pandemic has quickly caused us to rethink many of the ways that we approach educating our students. Whether we are in an urban, suburban or rural setting, the crisis has reaffirmed the importance of having effective teachers providing regular instruction to our students.

Additionally, a light has now been shone on what we have long known: that our most vulnerable students cannot always rebound from any disruption to regular instruction. The coronavirus has caused the most disruption to educating our students than any time in our history.

As of March 6, school closures due to coronavirus have impacted at least 124,000 U.S. public and private schools and affected at least 55.1 million students. Early on, we were all scrambling to ensure that students were able to access virtual instruction, obtain meals and ensuring that students and staff were safe, as most schools districts were closed through the rest of the school year. Now it is important to consider what actions need to be taken, particularly in supporting Principals, teachers and school-based instructional staff, when school reopens for the 2020-21 school year.

To use an overused term, even when we open up schools again, it will not be business as usual. We need to think about how to support our Principals, teachers and school-based instructional staff in healing from their own traumatic experiences and be ready to teach students who have had an uneven educational experience during school closures. Traditional approaches to mentoring, induction and professional development will not suffice. Just consider just a few of the following impacts on student learning:

- While many school districts provided Chromebooks and other devices to students, the coronavirus pandemic has highlighted the digital divide, as well widened the equity gaps in our nation. There has been an uneven transition to online learning and how students are being taught. Among the most significant differences are between the country’s poorest and wealthiest schools around access to basic technology and live remote instruction. Rural, urban and the highest poverty schools are less able to reach all students, and there are less students logging into instruction.

- The gap in education quality and socioeconomic equality is being further exacerbated.

- If schools start again in August or September 2020, on average, students will miss direct classroom instruction for 60-75 days, in addition to a summer break.

These significant impacts on students will directly influence how we must support both novice and experienced teachers and other instructional support staff to take on the significant challenges of opening up schools and welcoming our students back post-crisis.

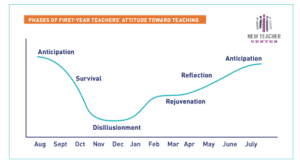

Teachers who were newly hired for the 2019-20 school year will still be considered novice teachers as they had only been teaching for 6 to 7 months before they were asked to transition to remote learning. Understanding the phases that novice teachers go through, the last few months of teaching for new teachers is critical. See the figure below.

In particular, March April, May and June are paramount to a new teacher’s development and attitude towards teaching. First-year teachers had to leave the classroom at a crucial time in their development – often just as they would begin renewing their sense of efficacy. It is unclear how the shift to online learning – essentially creating brand new structures – will impact their confidence-level and teaching capacity.

Additionally, more new teachers may be hired for the 2020-21 school year – that is, if the weakened economy does not force districts to reduce staff. Districts and schools will need to revisit—or in some cases—completely revamp traditional induction and mentoring programs to meet these unique needs of novice teachers and the challenges of a post coronavirus classroom.

Experienced teachers will also need a different kind of support. Usually, the focus for professional development is on content of new curriculum. However, in returning to school, professional development will need to focus on the additional challenges that students will bring when schools reopen. In many ways, experienced teachers are like new teachers as they will not have had the challenge of starting a school year after a situation that has been brought on by a pandemic. Experienced teachers, for example, who were on an improvement plan when school abruptly ended, should be given the additional opportunity, time and support to demonstrate improvement.

So, what can districts do to proactively plan for the Fall?

Now is the time for superintendents, central office staff and principals to consider and plan for the opening of school. The mindset should not be that the district is back to business as usual, but that this will be business as unusual. In many ways, Principals, teachers and support staff will become the first responders when school begins again. It is time for the central office to review programs and professional development plans for instructional staff. Here are some things to consider in planning:

- Reframe your view of what constitutes a new teacher. Next year, your new teacher class will be comprised of novice teachers from 2019-20 and 2020-21. What will this mean for your assignment of mentors/coaches and capacity to support and observe novice teachers? What will it mean for your Principals/Aps in terms of evaluation workloads?

- Consider your experienced teachers will need a re-start as well and may not be able to take on mentoring responsibilities as before. What will this mean in terms of individualized support and job-embedded professional development for experienced teachers? Are your coaches prepared to provide support?

- Prepare teachers to differentiate for student needs even more than they already do. Understand that students will return to school with uneven experiences from their time away from school. Teachers will need both time and supports to take on this monumental challenge.

- Understand that many leaders, teachers and other staff may have had trauma and loss, as well. Will schools be able to provide ongoing emotional support for instructional staff with crisis teams or employee assistance. Will the district be able to provide the emotional support that might be needed? It may be a time to consider small focus groups, affinity groups, or opportunities for instructional staff to collaborate and learn together. Given financial constraints it may be extremely challenging but if possible, the district may even want to increase planning time, perhaps after school.

- Anticipate that for high need schools, instructional staff returning from the pandemic sill have increased challenges due to the disruption. Research indicates that the highest-needs schools often have more novice teachers, alternatively certified teachers or teachers on provisional licenses. How will your district and schools provide the additional instructional support to these teachers in high-needs schools?

- Focus professional development on what type of instruction will be most effective for students who may need reorientation to school, reteaching, or remediation. Students need to recoup the many hours of lost learning time. How will schools provide needed professional development but not take teachers and instructional support staff out of the classroom?

The Coronavirus pandemic reminds us all that our Principals, teachers and frontline instructional staff are our best defense to combat the losses and increased equity gap of our students. There will be many challenges that school systems will be dealing with when schools are opened again. However, nothing is as important for district leaders to do then to ensure Principals, teachers and instructional support staff are supported and have the tools they need.

—-

Dr. Susan Marks has been privileged to be in public education for over 40 years. Susan is a Human Capital Partner with the Urban Schools Human Capital Academy (USHCA), a national nonprofit that develops, supports, and networks human resources and human capital leaders in schools, districts, charter organizations and states to drive measurable improvements in teacher and principal quality. Our belief is that the best people get the best results for students.